When the original SECURE Act was passed in December 2019, it brought sweeping changes to the post-death tax treatment of qualified retirement accounts. One of the biggest changes was to eliminate the prior "stretch" treatment of post-death distributions for most non-spouse beneficiaries, who are now subject to the so-called 10-Year Rule requiring beneficiaries to fully distribute inherited retirement accounts by the end of the 10th year following the original account owner's death.

In early 2022, when the IRS issued its initial Proposed Regulations regarding the SECURE Act's provisions, it included another bombshell: Not only would so-called "Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries" be subject to the 10-Year Rule, but, if the original account owner had been subject to Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) prior to their death, the beneficiary would also need to take annual RMDs throughout that 10-year period (in addition to fully distributing the account by the end of the 10th year).

And now, in its new Final Regulations issued on July 18, 2024, the IRS has confirmed the requirement for Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries to take RMDs annually (although for beneficiaries who would have been required to take RMDs in 2021–2024 but didn't, the IRS has confirmed that there will be no penalty and no requirement to make up the missed distribution, meaning the new regulation effectively starts with RMDs required to be taken in 2025).

Beyond the confirmation of the general post-death RMD rules, the 260-page Final Regulations document offers a slew of other regulatory guidance for specific circumstances where the new rules for Eligible and Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries apply. These include:

Along with the new Finalized Regulations, the IRS also released a new set of Proposed Regulations dealing with some unanswered questions around the SECURE 2.0 Act passed in late 2022. Most notably, the new Proposed Regulations confirm that the RMD age for individuals born in 1959 is 73 (since a drafting error in the final legislation inadvertently set that RMD age to both 73 and 75) and fill in rules around the SECURE Act's new provision allowing surviving spouses of retirement account owners to elect to be treated as the decedent for RMD purposes – although, as the Proposed Regulations make clear, the treatment for surviving spouses won't really be identical to the decedent's since the surviving spouse must still calculate RMDs based on their own life expectancy, and none of their own beneficiaries will qualify as Eligible Designated Beneficiaries.

As a whole, these regulations introduce significantly more complexity to the process of tax planning around retirement accounts, particularly after the death of the account's original owner. Which makes it all the more valuable for financial advisors to get familiar with the new rules and their planning implications for different circumstances, since clients will be more reliant on sound advice to give them clarity and help them avoid pitfalls when deciding what to do!

Jeffrey Levine, CPA/PFS, CFP, AIF, CWS, MSA is the Lead Financial Planning Nerd for Kitces.com, a leading online resource for financial planning professionals, and also serves as the Chief Planning Officer for Buckingham Strategic Wealth. In 2020, Jeffrey was named to Investment Advisor Magazine’s IA25, as one of the top 25 voices to turn to during uncertain times. Also in 2020, Jeffrey was named by Financial Advisor Magazine as a Young Advisor to Watch. Jeffrey is a recipient of the Standing Ovation award, presented by the AICPA Financial Planning Division for “exemplary professional achievement in personal financial planning services.” He was also named to the 2017 class of 40 Under 40 by InvestmentNews, which recognizes “accomplishment, contribution to the financial advice industry, leadership and promise for the future.” Jeffrey is the Creator and Program Leader for Savvy IRA Planning®, as well as the Co-Creator and Co-Program Leader for Savvy Tax Planning®, both offered through Horsesmouth, LLC. He is a regular contributor to Forbes.com, as well as numerous industry publications, and is commonly sought after by journalists for his insights. You can follow Jeff on Twitter @CPAPlanner.

Read more of Jeff’s articles + Read More +

Ben Henry-Moreland is a Senior Financial Planning Nerd at Kitces.com, where he specializes in writing and speaking on financial planning topics including tax, practice management, and technology. He also co-authors the monthly Kitces #AdvisorTech column. Drawing from his experience as a financial planner and a solo advisory firm owner, Ben is passionate about fulfilling the site’s mission of making financial advicers better and more successful.

Read more of Ben’s articles + Read More +

On the morning of July 18, 2024, the IRS released the long-awaited, much-anticipated new Final Regulations for Required Minimum Distributions (along with some new additional Proposed Regulations, just for good measure). The Final Regulations definitively answer many of the questions that have lingered since the enactment of the SECURE Act, and even more so since the IRS released its Proposed Regulations that shocked the planning world with its unexpected interpretation of the 10-Year Rule (that required annual distributions for some Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries during the period of time covered by the 10-Year Rule).

Since the release of the relevant Proposed Regulations in February of 2022, the #1 question on the minds of advisors and their clients has been, "Are beneficiaries going to be required to take annual minimum distributions during the 10-Year Rule?"

We now know the answer is "Yes, but ONLY if a beneficiary subject to the 10-Year Rule inherits from an owner who died on or after their Required Beginning Date (RBD)."

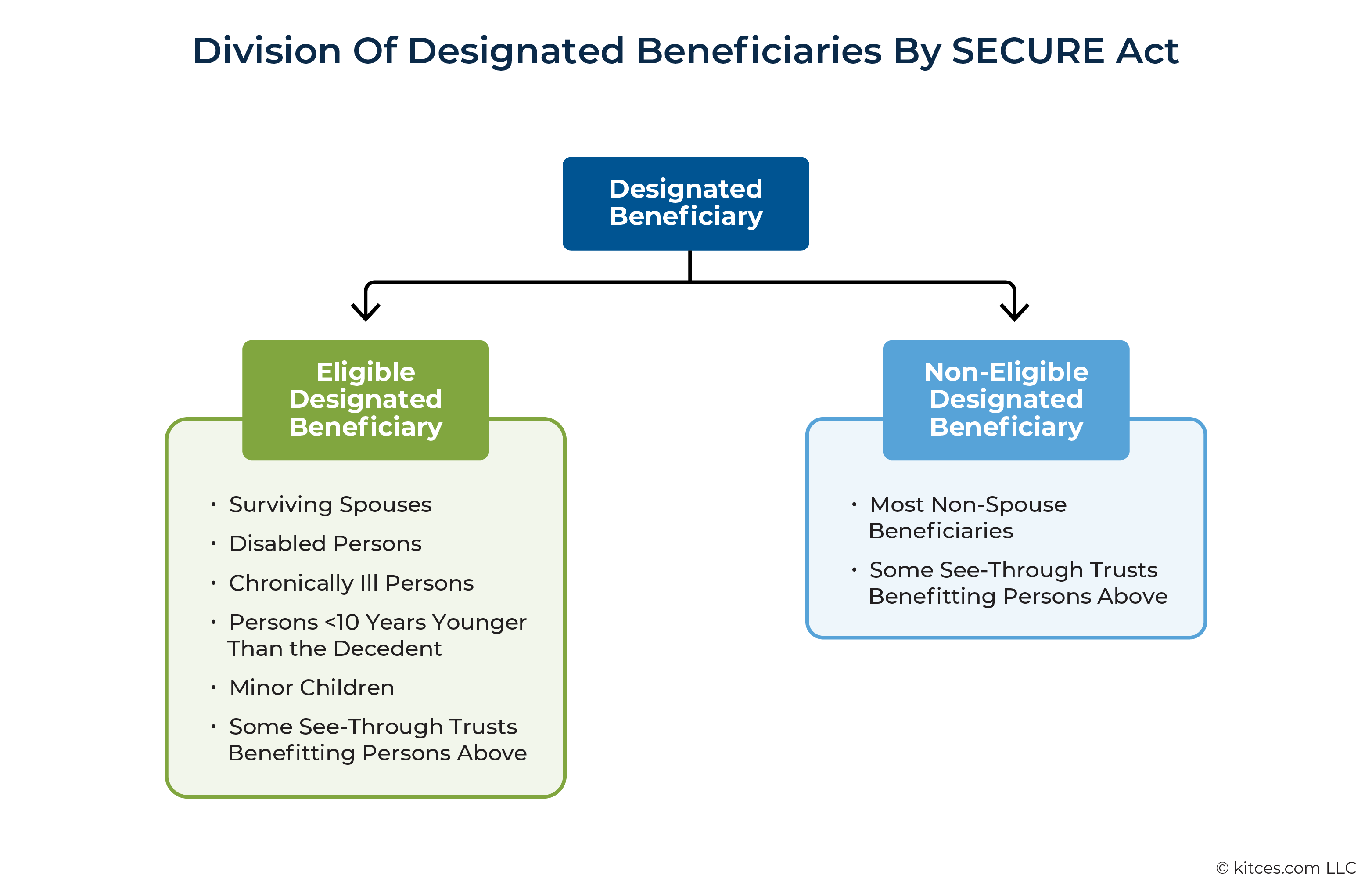

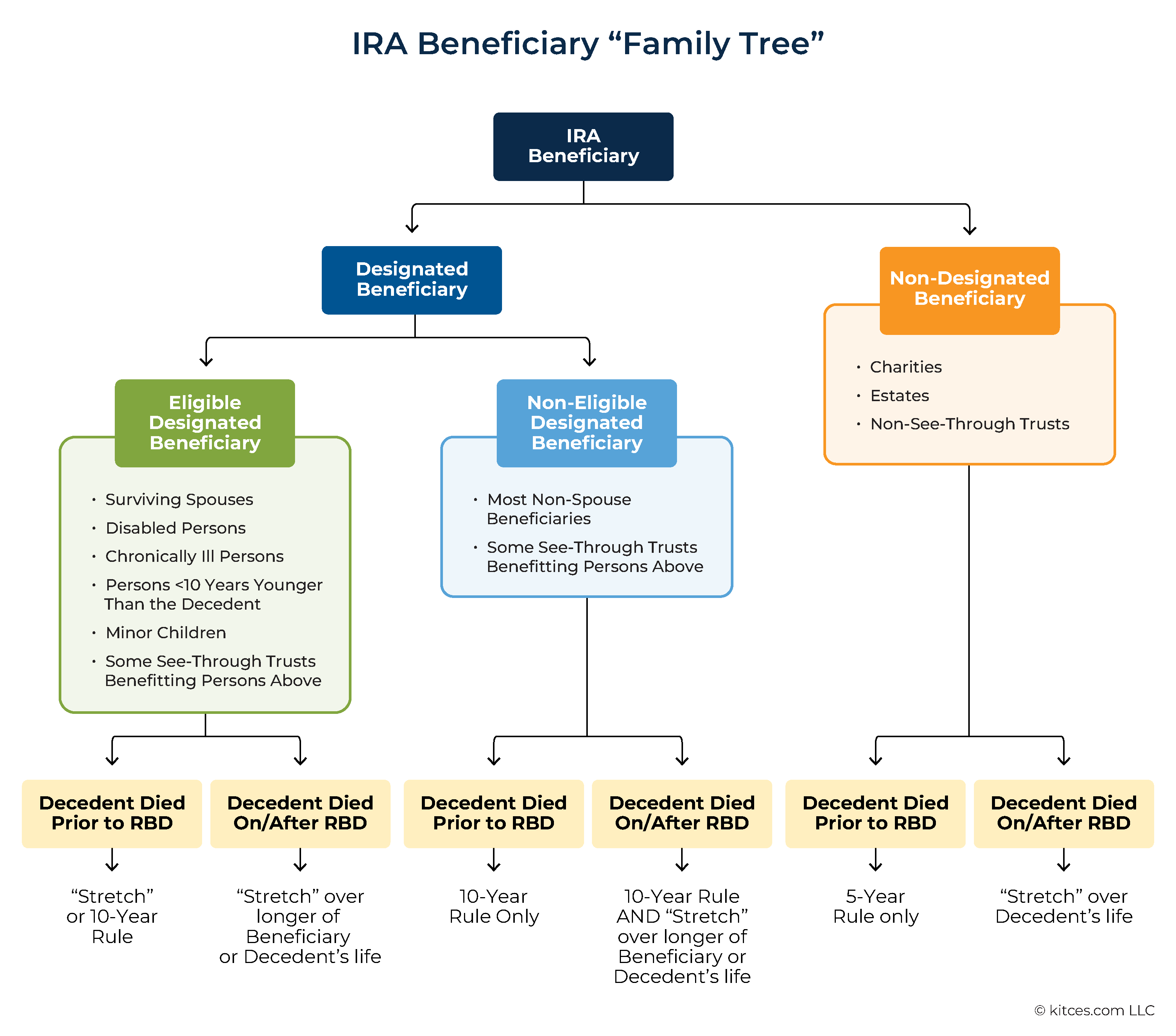

Readers may recall that the original SECURE Act split the old group of Designated Beneficiaries into 2 sub-categories: Eligible Designated Beneficiaries and Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries. The latter of these 2 groups (which encompasses most non-spouse beneficiaries) was then made subject to a new 10-Year Rule.

Simply stated, that 10-Year Rule provides that the entire balance of an inherited retirement account must be emptied by the end of the 10th year after the year of the owner's death.

Initially, everyone in the planning world assumed that the 10-Year Rule was a replacement for the "Stretch" rules that previously applied to those non-spouse Designated Beneficiaries. In other words, the thought was that all anyone in this new group of so-called Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries had to do to comply with the post-death distribution rules was 'just' to make sure that, by December 31st of the 10th year after the year they inherited the retirement account, everything was distributed, and the account balance was $0. Or, stated differently, the prevailing theory was that Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries could take as much or as little as they wanted in Years 1–9 after death, as long as it was all out by the end of Year 10 (after death).

But in February of 2022, the IRS threw everyone for a loop when it issued its Proposed Regulations. Specifically, the IRS took the group of Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries (which, itself, had 'just' been split out from Eligible Designated Beneficiaries by the text of the SECURE Act) and split it into 2 subgroups of its own:

And while the Proposed Regulations provided that the only thing the first subgroup of Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries (inheriting from an individual dying prior to their RBD) needed to do to comply with the post-death distribution rules was to empty the inherited retirement account by the end of the 10th year after death, the second subgroup of Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries (inheriting from an individual dying on/after their RBD) was required to comply with both the new 10-Year Rule and the 'old' Stretch rules.

The IRS's Final Regulations effectively mirror the Proposed Regulations, subjecting different requirements for 2 groups of Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries based on when the original account owner died. Thus, when planning for Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries, advisors must ascertain whether the owner died before or on/after their Required Beginning Date.

Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries who inherit(ed) a retirement account from someone who died before their Required Beginning Date only have to empty the inherited retirement account by the end of the 10th year after the owner's death.

By contrast, Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries who inherit(ed) a retirement account from someone who died on or after their Required Beginning Date are subject to both the 10-Year Rule and to the 'old' (but still applicable) Stretch rules. In other words, at a minimum, Stretch-style RMDs must be taken in years 1–9 after the year of death, with any and all remaining amounts in the account distributed by the end of the 10th year after death.

All together, these changes made by the SECURE Act have resulted in a system that, objectively, is a complicated mess maze of possibilities.

As a reminder, earlier this year, the IRS issued Notice 2024-35, which effectively waived the annual "Stretch" RMD requirement during the 10-Year Rule (for affected beneficiaries) for 2024. This followed similar guidance issued by the IRS in Notices 2022-53 and 2023-54, which waived the same RMDs in a similar manner for 2021, 2022, 2023, and 2024.

The end result is that, thanks to that collection of Notices, the intra-10-Year-Rule annual RMDs required under the Final Regulations (for Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries inheriting from an owner who died on/after their RBD) don't really apply until next year (2025). And, to the extent that an intra-10-Year-Rule distribution was (or is) not taken in 2021–2024, there is no penalty and no need to go back and make up the distribution in a future year.

Just because a client doesn't have to take a distribution this year doesn't mean they shouldn't. Many beneficiaries subject to the 10-Year Rule are best served by spreading the income from their inherited accounts out over as many years as possible in an effort to avoid a much larger spike in income (and tax rate) in a future year.

While no intra-10-Year-Rule annual distributions are required for years prior to 2025, to the extent applicable, any/all of those years still count towards a beneficiary's total time for the 10-Year Rule. So, the 10-year clock for a beneficiary inheriting in 2020–2023 still starts the year after death and not in 2025.

Example 1: Frayda is a Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary who inherited an IRA from her father in 2021. At the time of his death, Frayda's father was 80 years old and, thus, past his Required Beginning Date. As a result, Frayda is subject to both the 10-Year Rule and annual Stretch-style distributions.

Now, suppose that, to date, Frayda has taken no distributions from her inherited IRA. Thanks to the relief provided by the IRS in Notices 2022-53, 2023-54, and 2024-35, she will not be subject to any penalty for failing to take her annual Stretch-style RMD for 2022, 2023, or 2024.

Going forward, however, to comply with the rules set forth in the Final Regulations, beginning in 2025, Frayda must take annual Stretch-style RMDs. In addition, she must fully deplete the inherited IRA by 2031, the 10th year after the year of her father's death (and not 10 years after beginning annual distributions).

Death gets an individual out of just about everything when it comes to taxes (e.g., estimated tax payments are no longer necessary), except for having to take a Required Minimum Distribution. Notably, to the extent that an individual had not yet fully satisfied their RMD for the year at the time of their death, the RMD must be satisfied by their beneficiary/ies.

There are several provisions in the Final Regulations that relate directly to this matter. They are as follows:

Historically, this has been somewhat of a gray area, and the conservative play was to have the beneficiaries split the decedent's remaining RMD amount in proportion to their share of the inherited retirement account. With a modest change in language, the preamble to the Final Regulations now provides a definitive, taxpayer-friendly answer to the question:

The final regulations also restore flexibility from §1.401(a)(9)-5 in the 2002 final regulations relating to the required minimum distribution for the calendar year of the employee's death by providing that a required minimum distribution must be paid to "any beneficiary" in the year of death rather than to "the beneficiary". Thus, for example, if an employee who is required to take a distribution in a calendar year dies before taking that distribution and has named more than one designated beneficiary, then any of those beneficiaries can satisfy the employee's requirement to take a distribution in that calendar year (as opposed to each of the beneficiaries being required to take a proportional share of the unpaid amount).

Consider the following example:

Example 2: Clint is 80 years old and has a single IRA. Betty and Bobby, his 2 children, are named as equal (50%) beneficiaries of the IRA, and Clint's RMD for the year has been calculated at $20,000. Unfortunately, Clint dies in July, having only taken $5,000 of his total $20,000 RMD prior to his death.

Betty and Bobby must satisfy their father's remaining $15,000 RMD by the end of the year. However, even though they are equal (50/50) beneficiaries of the account, they do not have to satisfy the outstanding $15,000 RMD amount in equal amounts.

Rather, the 2 beneficiaries can satisfy the $15,000 remaining year-of-death RMD in any proportion they want. So, for instance, Betty could take a distribution of $15,000 to satisfy the requirement. Or she could take $10,000 while Bobby takes $5,000. Or they could each take $7,500. You get the point!

What happens, though, if an IRA owner has different beneficiaries for their different IRA accounts? How is the decedent's remaining year-of-death RMD allocated amongst the different IRA accounts (and subsequently, to the beneficiaries of those accounts)?

The Final Regulations provide a complex answer to this question, one that is rife with potential complications. In short, the decedent's remaining IRA RMD must be taken proportionately from each of the decedent's inherited IRAs.

More specifically, if an IRA owner has:

Then, the remaining year-of-death RMD must be taken proportionately from each of the owner's IRAs based on the prior-year-end values (adjusted as necessary for RMD purposes).

Example 3: Irma has 2 IRAs: IRA #1 and IRA #2. IRA #1 had a prior-year ending balance of $1,000,000 and is left to her 2 biological children, Bill and Ted. IRA #2 had a prior-year ending balance of $250,000 and is left to her 2 stepchildren, Tom and Jerry.

Now, suppose Irma's total IRA RMD for the year is $62,000 (combined RMD for both IRAs). Unfortunately, Irma dies in March, having only taken $12,000 of her year-of-death RMD prior to her passing.

The remaining $50,000 of Irma's year-of-death RMD must be taken by the end of the year. Additionally, since Irma meets all 3 conditions outlined above – that is, because she has 1) more than one IRA, 2) non-identical beneficiary designations for the 2 accounts, and 3) didn't take her full RMD for the year before her death – the Special Rule applies, and Irma's remaining RMD must be taken from her 2 accounts proportionally to their prior-year-end balances.

Irma's cumulative IRA balance as of the prior year's end was $1,000,000 (IRA #1) + $250,000 (IRA #2) = $1,250,000, so $1,000,000 ÷ $1,250,000 = 80% of Irma's cumulative IRA balance was in IRA #1, and $250,000 ÷ $1,250,000 = 20% of Irma's cumulative IRA balance was in IRA #2.

Thus, 80% of Irma's remaining $50,000 year-of-death RMD, or $40,000, must be taken from IRA #1 (by Bill and Ted, in any proportion they want, as described by the General Rule), and 20% of the remaining $50,000 year-of-death RMD, or $10,000, must be taken from IRA #2 (by Tom and Jerry, in any proportion they want, as described in the General Rule).

Apart from being complicated, there appear to be serious privacy issues raised by this regulation. For example, what if a client wants to discreetly leave money to 1 or more beneficiaries without other beneficiaries of a different account knowing they didn't get it all?

Under this Regulation, it would be obvious to beneficiaries of one account that there was other money left to other beneficiaries (or to the same beneficiaries, but in different percentages) because, if not, this rule wouldn't apply in the first place. With some quick back-of-the-napkin math, it would also be pretty easy to make a good estimate of the total value of the account(s) left to other beneficiaries.

From a tax-planning point of view, in general, waiting until later in the year to satisfy an RMD makes sense. That being said, clients in this situation may find the simplicity (and privacy) of taking an RMD as early as possible during the year more valuable than the potential tax benefits associated with taking the same distribution(s) later in the year.

But what if a beneficiary inherits a retirement account in, say, the beginning of December? Depending on a number of factors, including the speed at which the custodian reviews and processes the applicable paperwork, it may be difficult, if not impossible, for the beneficiary to complete all the steps necessary to have a distribution for the decedent's remaining year-of-death RMD processed prior to the end of the year.

The Proposed Regulations sought to address this matter by providing beneficiaries with an automatic waiver of the RMD penalty if they took the distribution by their tax filing deadline (including extensions) for the year in question. The Final Regulations provide even more time, giving most beneficiaries up to December 31st of the year after death to satisfy the decedent's year-of-death RMD in order to qualify for the automatic penalty waiver.

In the very limited situation where the beneficiary's filing deadline, plus extensions, extends beyond December 31st of the year after death (e.g., when a filing deadline is extended due to a natural disaster), the deadline to take the decedent's year-of-death RMD (and qualify for the automatic waiver) is the beneficiary's filing deadline, including any extensions.

In addition to the headline rules around post-death RMDs for retirement account owners and beneficiaries, the Finalized Regulations also include a slew of other RMD-related guidance to fill a number of gaps left by the original text of the SECURE Act.

The Final Regulations offer some good news for surviving spouses, as well as some bad news. First, the good news: Under the Proposed Regulations, the ability to make a spousal rollover was, for the first time, going to be subject to a deadline. More specifically, the Proposed Regulations stated the following:

…a surviving spouse must make that election by the later of (1) the end of the calendar year in which the surviving spouse reaches age 72, and (2) the end of the calendar year following the calendar year of the IRA owner's death.

The Final Regulations eliminate this deadline, leaving surviving spouses with the same open-ended ability to treat a decedent's account as their own as they have long been permitted to.

The bad news is that some surviving spouses will be stuck dealing with "Hypothetical RMDs." (As if 'real' RMDs aren't bad enough!?)

Notably, one of the more surprising rules in the February 2022 Proposed Regulations was the introduction of a new "Hypothetical RMD". While such Hypothetical RMDs can be found nowhere in the Tax Code, the IRS felt that such a rule was necessary to prevent certain surviving spouses from using the 10-Year Rule to delay RMDs.

Despite some significant opposition to the rule, the IRS chose to keep the concept of the Hypothetical RMD 'alive' in the Final Regulations. In short, to the extent a surviving spouse initially uses the 10-Year Rule and later decides that they'd like to treat the deceased spouse's IRA as their own (or complete a spousal rollover), they will first need to 'make up' any RMDs they would have needed to have taken, had the funds hypothetically been in their IRA all along.

Example 4: Jack and Jill were each 70 years old when Jack died in 2021. Jill didn't want or need any money from Jack's IRA at the time, so she chose to leave it in an inherited IRA and elected to use the 10-Year Rule.

Since Jack died prior to his Required Beginning Date, Jill would have no annual RMD requirements during the period of time covered by the 10-Year Rule. Accordingly, all Jill needs to do is empty the account by 2031.

Suppose now that in 2030, Jill decides that she doesn't want to have to empty the account in the following year. To avoid such a requirement, Jill wants to make a spousal rollover of the inherited IRA into her own IRA. She may do so, but only after she has satisfied a hypothetical RMD requirement.

Essentially, Jill must calculate the RMD she would have needed to take in every year beginning in 2024 (the year she turns 73) and going all the way through 2030 had the funds been in her own IRA the whole time. Only after taking a distribution of this amount (or more) would Jill be allowed to roll over the balance of the funds to her own IRA (and avoid a complete distribution).

While the Final Regulations allow an Eligible Designated Beneficiary to choose between either the "Stretch" rules or the 10-Year Rule, a plan can require such beneficiaries to use either the Stretch method or the 10-Year Rule.

In addition, the Final Regulations clarify that a plan can have different rules for different categories of Eligible Designated Beneficiaries. For example, a plan can allow a surviving spouse to choose between the Stretch or the 10-Year Rule (or to elect to be treated as the decedent, as described in more detail in the section below on the new Proposed Regulations) while requiring all other Eligible Designated Beneficiaries to use the 10-Year Rule.

Accordingly, to the extent that a retirement account owner names one or more Eligible Designated Beneficiaries as a beneficiary of an account, the post-death distribution rules for such beneficiaries could be an important factor when deciding whether to roll funds to another plan or IRA.

For Eligible Designated Beneficiary purposes, when determining if an individual is a "minor child of the decedent", they will be considered a minor until they reach their 21st birthday.

The age at which the minor actually reaches the age of majority under state law is irrelevant for this purpose, as is whether the child is still in school. Upon reaching the age of majority (at 21), the 10-Year Rule begins to apply to such beneficiaries.

Additionally, the Final Regulations require such (formerly) minor children to continue taking annual Stretch-style RMDs during the period covered by the 10-Year Rule, regardless of whether the decedent died before, on, or after their Required Beginning Date.

Under the SECURE Act, beneficiaries who are either "disabled (within the meaning of section 72(m)(7))" or ''chronically ill… (within the meaning of section 7702B(c)(2)" whose chronic illness is indefinite or reasonably expected to be lengthy in nature are Eligible Designated Beneficiaries. Notably, the Final Regulations largely retain time-sensitive documentation requirements first put forth by the IRS in its Proposed Regulations.

Specifically, in order for an individual to be considered disabled or chronically ill for purposes of being an Eligible Designated Beneficiary, they must provide appropriate documentation to the employer-sponsored retirement plan by October 31st of the year after the year of the original account owner's death. And if the appropriate documentation is not provided in a timely manner, then the beneficiary will not be considered an Eligible Designated Beneficiary and will be subject to the 10-Year Rule, regardless of how disabled and/or chronically ill they are.

For beneficiaries who are disabled, the specific documentation to be provided depends on the facts and circumstances of their disability. For instance, if the individual is currently considered "disabled" for purposes of Social Security benefits, documentation confirming said determination by the Social Security Administration is sufficient. Alternatively, the beneficiary could provide other documented evidence, such as a note from a physician, confirming that they are "unable to engage in any substantial gainful activity by reason of any medically determinable physical or mental impairment that can be expected to result in death or to be of long-continued and indefinite duration."

By contrast, the documentation rules for individuals who are chronically ill are much more rigid (and are explicitly provided for in the text of the SECURE Act). Notably, in order to be considered chronically ill for purposes of qualifying as an Eligible Designated Beneficiary, the individual must provide the employer plan with certification from a licensed healthcare professional.

According to the Final Regulations:

…an individual will be treated as chronically ill under section 7702B(c)(2)(A)(i) only if there is a certification from a licensed health care practitioner (as that term is defined in section 7702B(c)(4)) that, as of the date of the certification, the individual is unable to perform (without substantial assistance from another individual) at least 2 activities of daily living and the period of that inability is an indefinite one that is reasonably expected to be lengthy in nature.

Critically, beneficiaries with a disability or chronic illness who inherited after the effective date of the SECURE Act, but in years prior to 2024, are not exempt from this requirement. However, such individuals (generally a beneficiary who is disabled or chronically ill and who inherits on or after January 1, 2020, and before 2024) are granted an extension of the typical deadline on October 31st of the year after the owner's death, and instead, have until October 31, 2025, to provide the employer-sponsored retirement plan with the required documentation.

While the post-death distribution rules for defined contribution employer plans and IRAs are generally the same, the documentation requirements related to an individual's disability and/or chronic illness are one of the exceptions to the common rules. Specifically – and rather curiously – the Final Regulations exempt beneficiaries of inherited IRAs from this requirement.

Thus, as long as an IRA beneficiary is disabled or is chronically ill (but for an indefinite period of time or what is reasonably expected to be lengthy in nature) within the meaning of the SECURE Act, they are an Eligible Designated Beneficiary. Thus, they can take Stretch distributions from the inherited IRA without having to provide the IRA custodian any proof of their condition.

If 1 or more of a retirement account owner's beneficiaries are disabled and/or chronically ill, the relative simplicity and privacy provided by an IRA (due to the lack of a documentation requirement) mentioned earlier could be an important factor to consider whether a rollover from a plan to an IRA would make sense.

One of the more interesting provisions to make its first appearance in the Final Regulations is a rule that says if a plan participant's "entire interest" in the plan is in a Designated Roth Account, they will be deemed to have died prior to their Required Beginning Date. This is an important distinction given the different treatment afforded to Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries based on whether the plan participant died prior to or on/after their Required Beginning Date (RBD).

Thankfully, to the extent that a plan participant has all of their plan balance in a Designated Roth Account, their Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries will not be required to take any distributions during years 1–9 after their death, allowing for the inherited Roth account to continue compounding as much as possible for 10 years.

Unfortunately, the Final Regulations are very specific about this benefit applying only if the entire plan balance is in a Designated Roth Account. Thus, if just a single dollar were to remain in the Traditional portion of the plan (e.g., Traditional 401(k) or 403(b) plan), and the individual died after reaching their RBD, the funds in the Designated Roth account would be subject to annual distributions during the period of time covered by the 10-Year Rule.

Most plan participants will not have their entire plan balances in the Roth portion of their plan. In such situations, where a significant Roth balance exists and where one or more beneficiaries will be subject to the 10-Year Rule, there may be a significant benefit to rolling over the plan Roth funds to a Roth IRA. The death of a Roth IRA owner will always be considered as taking place before their RBD (even if they have Traditional IRA money as well), and, thus, their beneficiaries will never be subject to annual distributions during the 10-Year Rule.

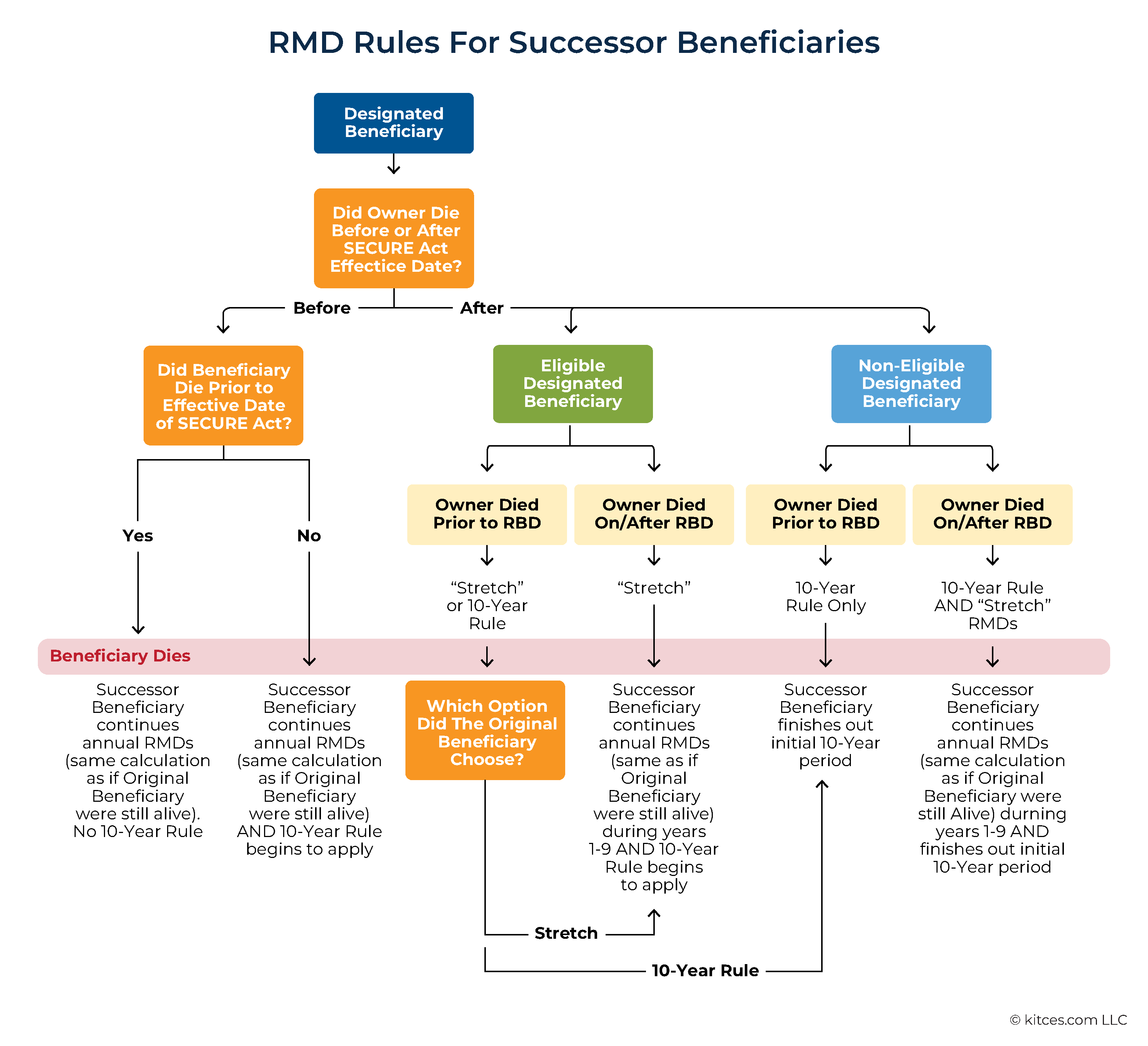

The rules for 'regular' beneficiaries are complicated, but unfortunately, they're not nearly as complicated as the rules for successor beneficiaries (the beneficiary of a beneficiary). That's because, under the Final Regulations, the rules that apply to a Successor Beneficiary vary based on a substantial number of factors, including whether the retirement account owner died before or after the SECURE Act's effective date, whether the beneficiary died before or after the SECURE Act's effective date, whether the original beneficiary was an Eligible Designated Beneficiary or Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary, and whether the retirement account owner died before or on/after their Required Beginning Date!

While the precise RMD requirements for a successor beneficiary can vary rather significantly, there are, at a minimum, 2 blanket statements that can be made about the rules for such persons, assuming that the original beneficiary died after the SECURE Act's effective date:

Candidly, for most advisors, it's probably not worth trying to commit the precise rules that apply to each and every situation to memory. Rather, it's important to know that the rules are complicated and that distribution requirements for a successor beneficiary can be very different depending upon the facts and circumstances, and also to have a resource to use to figure out the precise rules that apply to a specific client situation if/when the need arises.

With that in mind, the flowchart below summarizes the rules for successor beneficiaries.

The original SECURE Act had a significant impact on the tax consequences of naming a trust as the beneficiary of a retirement account. Although it kept much of the existing structure of trusts as account beneficiaries, the SECURE Act created much more complexity around what happens within that structure when a trust is named as an account beneficiary.

Most importantly, the SECURE Act's creation of Eligible and Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries, with Stretch distribution treatment applying only to Eligible Beneficiaries, meant that it now mattered whether some or all of a trust's beneficiaries consisted of Eligible Designated Beneficiaries or Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries.

A trust whose beneficiaries were only Eligible Designated Beneficiaries would still be able to receive distributions over those beneficiaries' life expectancies based on the age of whomever is the oldest (as was the case prior to the SECURE Act). However, the existence of any Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries would cause the entire trust (and, by extension, all of its beneficiaries) to become subject to the 10-Year Rule.

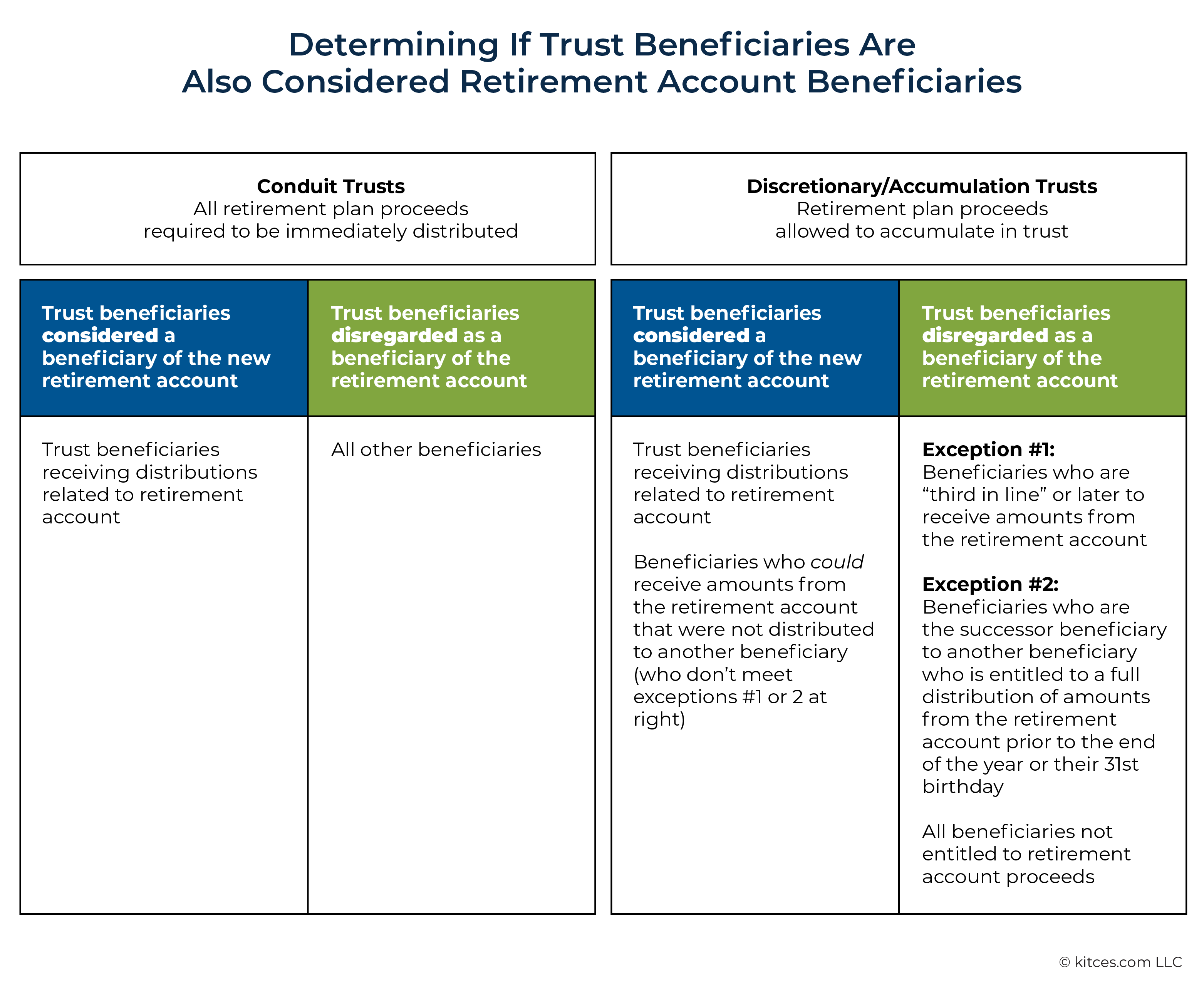

The original Proposed Regulations and the new Final Regulations built on existing rules concerning which beneficiaries of the trust are also treated as beneficiaries of the retirement account (or are instead disregarded from being treated as retirement account beneficiaries). This matters because the distinction can dictate whether or not the trust is considered a See-Through Trust (which allows the beneficiaries, rather than the trust itself, to be treated as the beneficiaries of the decedent's retirement account when the trust is named as the beneficiary of a retirement account).

Further, if the trust is considered a See-Through Trust, determining whether it is a Conduit or Accumulation trust (depending on whether retirement account proceeds are required to be distributed immediately to the beneficiaries or allowed to accumulate within the trust) can ultimately determine whether the Stretch or 10-Year Rule applies to distributions to the trust and its beneficiaries.

Namely, in a Conduit Trust, where all distributions from the retirement account are required to be immediately distributed to one or more trust beneficiaries, only the trust beneficiary initially designated to receive the distributions is treated as a retirement account beneficiary. All other trust beneficiaries are disregarded for purposes of determining the retirement account's post-death distribution schedule.

In an Accumulation Trust, in which distributions from the retirement account are allowed to accumulate within the trust, both "Primary Beneficiaries" (who can receive retirement account proceeds within the trust without that access being contingent on the death of another beneficiary) and "Residual Beneficiaries" (who could receive undistributed retirement account proceeds after the death of a Primary Beneficiary) are treated as beneficiaries of the retirement account, with 2 exceptions:

While not making any changes to these rules, the Finalized Regulations do make 2 clarifications.

First, in the preamble to the Final Regulations, the IRS specifies that if a residual beneficiary has any access to accumulated retirement account distributions in the trust during the lifetime of a Primary Beneficiary, even if that access is restricted in some way, they will be treated as a beneficiary of the retirement account. For example, if a residual beneficiary is able to receive distributions only for purposes of health, education, maintenance, and support during the lifetime of a primary beneficiary, they would still be considered to have access to the accumulated retirement account distributions and would be considered a retirement account beneficiary.

Second, the Final Regulations clarify that payments "for the benefit of" a trust beneficiary are treated as if they are direct payments to the beneficiary. For example, trust distributions that go to a custodial account for the benefit of a minor beneficiary rather than to the beneficiary themselves are still treated as if they were paid directly to the beneficiary.

As shown below, advisors will need to determine both the type of trust – Conduit or Discretionary/Accumulation – and the specific conditions that allow beneficiaries to access amounts related to the retirement account's distributions in order to determine whether each trust beneficiary will be included or disregarded as retirement account beneficiaries (therefore affecting whether the trust can receive Stretch treatment or be subject to the 10-Year Rule).

An important new feature in the Final Regulations pertains to trusts that provide for themselves to be divided into separate trusts for each of their multiple beneficiaries immediately upon the death of the retirement account owner. For these trusts, the RMD rules will be applied to each individual trust beneficiary according to their own status as an Eligible or Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary – not, as the current regulations require, to all beneficiaries uniformly according to the beneficiary with the shortest withdrawal schedule.

Example 5: Joe is the owner of a retirement account who designates a See-Through Trust as the beneficiary of the account. The trust's beneficiaries are Joe's 5 sons, Jackie (age 25), Tito (age 23), Jermaine (age 22), Marlon (age 18), and Michael (age 11). Per the terms of the trust, immediately upon Joe's death, the trust will be divided into 5 separate sub-trusts with each brother as the sole beneficiary of each.

Prior to the release of the Final Regulations, the distribution timeline for the retirement account would have been the same across all of the trust beneficiaries according to whomever had the shortest distribution schedule. And since Jackie, Tito, and Jermaine are considered Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries (since they are all over the age of majority), all of the beneficiaries would be subject to the 10-Year Rule.

Under the new regulations, however, the division of the trust into separate sub-trusts means that each beneficiary will receive their own distribution schedule according to their own beneficiary status. Which means that Marlon and Michael (who are both considered Eligible Designated Beneficiaries since they are under the age of majority) will both get to Stretch their distributions according to their life expectancy (at least until they reach the age of majority), while Jackie, Tito, and Jermaine, as Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries, will remain subject to the 10-Year Rule.

In the Proposed Regulations, this treatment was only allowed for specified Applicable Multi-Beneficiary Trusts that had at least one beneficiary who was disabled or chronically ill (but also had other non-disabled beneficiaries). The expansion of this rule to include all types of see-through trusts means that, for trusts that are structured to divide into separate sub-trusts for each beneficiary, the fact that there may be Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries among the trust beneficiaries would not cause any Eligible Designated Beneficiaries to lose their Stretch distribution treatment.

Notably, in order to be eligible for treatment as a separate account, a trust must already be a See-Through Trust. So, for example, if a charity were named as a trust beneficiary (and didn't otherwise meet the above rules to be disregarded as a beneficiary of the retirement account) alongside other human beneficiaries, the trust would not be considered a See-Through Trust because the charity is not an "identifiable" beneficiary. And so even if the trust provided that it would be divided into separate sub-trusts for each beneficiary, the entire trust would be considered a Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary subject to the much harsher 5-Year Rule.

Also, in order to receive this treatment, the Final Regulations specify that there can be no discretion in how distributions from the retirement account are allocated to each individual sub-trust. In other words, the trust document must specify how allocations to each sub-trust are determined – they can't be decided after the fact by the trustee or any other individual.

The Final Regulations retain the original Proposed Regulations' provision that allows an individual to hold and exercise a power of appointment over a See-Through Trust after the death of the retirement account owner. If the power of appointment is exercised or restricted to a limited group of identifiable beneficiaries on or before September 30 of the year of the original account owner's death, those new trust beneficiaries will be considered beneficiaries of the retirement account. Otherwise, the holder of the power of attorney, plus any subsequent beneficiaries who are added, will all be considered retirement account beneficiaries.

A similar rule allows for any modifications to the trust terms after the original account owner's death that are pursuant to state law, which may add or remove beneficiaries to the trust. If such modifications are made by September 30 of the year following the account owner's death, they are treated as they had always been the terms of the trust, meaning that any added trust beneficiaries will be treated as retirement account beneficiaries, and any removed trust beneficiaries will be disregarded for retirement account purposes.

However, if the modifications occur after the September 30 deadline, the added beneficiaries will be considered retirement account beneficiaries beginning in the year after they were added, while removed trust beneficiaries will continue to be regarded as retirement account beneficiaries going forward.

Finally, if the addition of a beneficiary necessitates the full distribution of the retirement account, then the full distribution is required by the end of the year following the beneficiary's addition. For example, if a trust has only Eligible Designated Beneficiaries, those beneficiaries can take Stretch distributions over the life expectancy of the oldest beneficiary. But if, after 15 years, the trust is modified to add a Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary, this change would subsequently subject all of the trust's beneficiaries to the 10-Year Rule and necessitate a full distribution of the retirement account since the trust has already 'outlasted' the 10-year distribution period. Per the Final Regulations, the full distribution would need to happen by December 31 of the year after the beneficiary was added.

The SECURE Act created a new trust designation known as an Applicable Multi-Beneficiary Trust, defined as a See-Through Trust with multiple beneficiaries, at least one of whom is disabled or chronically ill. The original Proposed Regulations provided for 2 types of Applicable Multi-Beneficiary Trust:

In both cases, beneficiaries with disabilities or chronic illnesses would be allowed Stretch treatment of the retirement account distributions, whereas otherwise, the inclusion of other Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries as trust beneficiaries would have forced all of the trust's beneficiaries to use the 10-Year Rule.

However, the Final Regulations expanded the "separate account" treatment afforded to Type I Applicable Multi-Beneficiary Trusts to all trusts that provide to be split into sub-trusts for each beneficiary (regardless of whether any of the beneficiaries was disabled or chronically ill). Which means there is no longer any need for Type I trusts to exist. Accordingly, the Final Regulations include only the Type II definition of an Applicable Multi-Beneficiary Trust.

The original SECURE Act's definition of an Applicable Multi-Beneficiary Trust specified that all of the trust's beneficiaries must be Designated Beneficiaries – meaning that there could be no non-human beneficiaries, even ones that couldn't access retirement account distributions within the lifetime of beneficiaries with disabilities. However, the SECURE 2.0 Act modified that rule so that certain charitable organizations may be treated as Designated Beneficiaries solely for the purpose of being included in an Applicable Multi-Beneficiary Trust.

The Final Regulations also clarified that, even though no other beneficiary can access retirement account distributions in an Applicable Multi-Beneficiary Trust during the lifetime of a beneficiary who is disabled or chronically ill, the trust may still provide for their interest in the trust to be terminated (e.g., to preserve eligibility for Medicaid or Supplemental Social Security benefits). In that case, it can still qualify as an Applicable Multi-Beneficiary Trust as long as the trust provides that the other trust beneficiaries cannot receive any amounts from the trust until after the death of the beneficiary with the disability or chronic illness, regardless of whether that beneficiary's interest in the trust is terminated.

The Final Regulations retain the Proposed Regulations' requirement that, in all cases when trusts are the beneficiaries of an employer retirement plan, the trustee must provide documentation to the plan administrator consisting of either 1) the trust instrument itself, or 2) a list of all beneficiaries of the trust (as of September 30 of the year following the original account owner's death), with a description of the conditions in which each beneficiary would be entitled to assets from the trust. This documentation must be provided by October 31 of the year following the account owner's death.

However, the Final regulations clarify that, as is the case with retirement plan beneficiaries who are disabled or chronically ill, the documentation rules for trust beneficiaries only apply to employer-sponsored retirement plans. In the case of IRAs, there is no requirement to provide trust documentation to the IRA custodian.

The SECURE 2.0 Act allowed participants in an employer plan who hold an annuity in their account to aggregate the annuity's value (defined as the present value of the annuity's future payments as of December 31 of the previous year) with that of their non-annuity assets for the purposes of calculating the entire account's RMD. However, the SECURE 2.0 legislation applied this treatment only to employer plans.

In the new Final Regulations, however, the IRS extended that treatment to IRAs as well. Individuals who own annuities within IRAs can aggregate their annuity and non-annuity IRA assets together to calculate their RMD and count the entire amount of their annuity payments against that RMD total.

Example 6: James is an unmarried 80-year-old retiree. He owns 2 IRAs: one holding $500,000 of non-annuity assets and the other holding an annuity that pays him $1,000 per month. As of December 31st of last year, the present value of the annuity was $100,000.

Under the new regulations, James is able to aggregate the annuity and non-annuity IRAs for the purposes of calculating his RMD and applying his account distributions to the required amount.

At age 80, James' life-expectancy factor used to calculate his RMD is 20.2. Under the new regulations, his RMD is ($100,000 + $500,000) ÷ 20.2 = $29,702.97. Additionally, he can apply all $12,000 of his annuity payments against this amount, meaning he will need to distribute the remainder, or $29,702.97 − $12,000 = $17,702.97 from the non-annuity IRA.

Under the old rules, James would have only been able to apply his life-expectancy factor against his non-annuity IRA, giving him an RMD of $500,000 ÷ 20.2 = $24,752.48 for the non-annuity IRA, with none of his $12,000 of payments from the annuity IRA counting against that total. So effectively, James would have needed to distribute $24,752.48 (the RMD for the non-annuity IRA) + $12,000 (the total annuity IRA payments for the year) = $36,752.48 from his retirement account under the previous regulations.

In other words, the new regulations reduce James' 'effective' RMD from $36,752.48 to $29,702.97.

Annuities in retirement plans may have a number of payment options available, including single-life, joint-and-survivor, and/or any number of period-certain options. In the case of a single-life annuity, the annuity's payments cease upon the owner's death; but with joint-and-survivor and period-certain annuities, the annuity's payments may continue after the retirement owner passes away. Which means it would be time to consider how those post-death payments interact with the SECURE Act's rules around post-death retirement account distributions.

The new Final Regulations provide that, in the event that payments from an annuity are held in a retirement account following the death of the account owner, those payments must cease before the date on which the account is required to be fully distributed – i.e., at the end of the 10th year after the original owner's death for a Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary, or when the "applicable denominator" (i.e., the number used to calculate the RMD amount based on life expectancy, which varies based on the status of the beneficiary) reaches 1 for an Eligible Designated Beneficiary.

In most cases, the surviving payee of a joint-and-survivor annuity will be the spouse of the original account owner, which means they will be considered an Eligible Designated Beneficiary who can receive Stretch distributions over their remaining life expectancy. Unless they reach the age where their applicable denominator reaches 1, they'll still be able to receive payments from the annuity for the remainder of their lifetime. However, in cases where, for whatever reason, the surviving annuitant is a Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary, their annuity payments will need to stop after 10 years, regardless of what the annuity contract actually provides for.

The Final Regulations do carve out one notable exception to this rule: In the case of a joint-and-survivor annuity where the annuitants were married as of the annuity starting date but later divorced (which could have otherwise made the ex-spouse a Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary if they hadn't met any of the other criteria and were thus subject to the 10-Year Rule), the surviving ex-spouse would still be treated as an Eligible Designated Beneficiary.

One other new rule introduced in the Final Regulations that doesn't fall into any of the above categories concerns amounts that are treated as distributed from an IRA on account of either 1) the IRA owner engaging in a prohibited transaction (such as performing maintenance or repair work on real estate property owned by the IRA, which can result in the deemed distribution of the entire IRA), or 2) the IRA acquiring "collectibles" as defined in IRC Sec. 408(m) (in which the cost of the acquisition is treated as being distributed from the IRA).

For an IRA owner required to take RMDs, any amounts treated as distributed from the IRA for either of these reasons do not count towards the owner's RMD requirement for the year – in the IRS's estimation, the tax consequences of those transactions wouldn't serve as enough of a deterrent if the IRA owner weren't also required to take their full RMD for the year.

Although, as the IRS notes in its commentary on the Final Regulations, if the IRA owner had $0 IRA assets left after one of the deemed distributions above, their RMD for the year would also be $0, as the RMD amount cannot exceed the IRA balance on the date of the distribution.

As if 260 pages of new Finalized Regulations weren't enough for advisors to wrap their minds around, the IRS also saw fit to release 36 more pages of new Proposed Regulations relating to retirement accounts. Thankfully, these new rules don't look nearly as impactful for retirees and beneficiaries as those contained in the Finalized Regulations, but they still contain a few important items.

In Congress's rush to pass the SECURE 2.0 legislation in the closing days of 2022, they let a significant drafting error slip through the final vote. The law's provisions that step up the age for beginning RMDs from 72 to 73 to 75 accidentally specified that people born in 1959 would be required to begin RMDs at two ages, 73 and 75.

The new Proposed Regulations start off by clarifying that the age when people born in 1959 will be required to begin RMDs is…

It's confirmed, then, that the final (for now) timeline for RMD beginning ages under SECURE 2.0 is:

As discussed earlier, the new Final Regulations specify that, in an employer plan, any portion of the employee's account held in a Designated Roth account is not included when adding up the account balance used to calculate the RMD for that year.

The new Proposed Regulations add to that guidance, clarifying that any amounts distributed from a Designated Roth account don't count towards fulfilling the individual's RMD requirement for the year either. In other words, only non-Roth dollars in the account count when calculating the RMD, and only non-Roth dollars distributed from the account count when it comes to fulfilling the RMD.

The upshot of this rule is that, since any part of a distribution that's treated as an RMD is not eligible to be rolled over into another retirement account, distributions from a Designated Roth account made after a participant reaches their RMD beginning age are fully eligible to be rolled over into, for example, a Roth IRA.

Prior to the SECURE 2.0 Act, surviving spouses of deceased retirement plan owners already had several options for what to do with the account (e.g., rolling the decedent's account into their own IRA, keeping the account separate but electing to treat it as their own, or keeping the account as-is and remaining as an Eligible Designated Beneficiary subject to Stretch distributions). SECURE 2.0's passage introduced yet another option for surviving spouses: the ability to elect to be treated as the deceased spouse and to delay RMDs until the year the deceased spouse would have been required to begin taking them.

The new Proposed Regulations provide guidance on this election, as discussed below. In doing so, however, the IRS makes it clear that the election will not be a simple matter of being treated "as the deceased spouse" in all regards.

The new election is available only to surviving spouses whose RMDs from the account would begin in 2024 or later. For example, if a retirement plan's original owner would have reached their RMD beginning date in 2024 but died in 2017 and left their retirement account to their spouse, then the spouse (who would be required to begin RMDs from the account in 2024) would be eligible to make the election. But if the original owner would have reached their RMD beginning date in 2023 instead of 2024, the surviving spouse would be required to begin RMDs in 2023, and wouldn't be able to make the election.

The Proposed Rules also clarify that if a retirement account owner died in 2023 having already reached their RMD age, their surviving spouse would be eligible to make the election, since in that case the surviving spouse's first RMD would be made in the year after the decedent's death, i.e., 2024.

The new Proposed Regulations specify that the election for a surviving spouse to be treated as their deceased spouse will be made automatically if the decedent was an employee who died before reaching their RMD beginning date. However, if the employee dies after their RMD beginning date, the election does not necessarily happen automatically. In this case, the terms of the retirement plan can specify whether the election will be made by default or if the surviving spouse will have to make it proactively.

The surviving spouse who has made the election to be treated as the decedent begins taking RMDs in the year that the original owner's RMDs would have begun. However, the amount of the RMD itself isn't necessarily identical to what the original owner's RMD would have been. Instead, the calculation depends on whether or not the original owner died before or after their RMD beginning date.

If the original owner died before their RMD beginning date, the surviving spouse is required to calculate their RMD using the Uniform Life Table and their own age as the basis for the calculation.

Example 7: John (age 70) is the owner of a retirement account for which his wife Linda (age 75) is the sole beneficiary. John dies this year, and Linda elects to be treated as the decedent for RMD purposes.

Assuming John was born in 1954, his RMD beginning age would have been 73. Linda is able to delay RMDs from John's account until the year he would have turned 73, at which point she would be 78.

The retirement account's value was $1 million as of December 31 of the prior year. To calculate Linda's first RMD from the account, the year-end value of $1 million is divided by the distribution period from the Uniform Life Table for Linda's age (78), which is 22.0.

So Linda's RMD is $1 million ÷ 22.0 = $45,454.54

If the original owner died after their RMD beginning date, however, the surviving spouse must use the greater "applicable denominator" between the (1) the Uniform Lifetime Table number using the surviving spouse's age; or (2) the Single Life Table number using the deceased spouse's age in their year of death, minus 1 for every subsequent year. In most cases, this will just be the surviving spouse's life expectancy as in the example above, but in cases where the surviving spouse is more than 10 years older than the deceased spouse, it could lead to using the deceased spouse's life expectancy.

Example 8: Trisha (age 75) is the owner of a retirement account for which her husband Garth (age 89) is the sole beneficiary. Trisha dies this year, and Garth elects to be treated as the decedent.

Because Trisha has already reached her RMD age, Garth will need to begin RMDs from the account starting next year. To calculate his RMD, he uses the greater of the number on the Uniform Lifetime Table for his own age of 90 that year (12.2), or the amount on the Single Life Table for Trisha's age of 75 this year minus one (14.8 − 1 = 13.8). Because the amount for Trisha's age is greater, that's the number used to calculate the RMD.

Assuming a $1 million account balance at year-end, Garth's RMD for 2025 would be $1 million ÷ 13.8 = $72,463.77.

So while the election for the surviving spouse to be treated as the deceased spouse may allow the surviving spouse to delay RMDs until the deceased spouse would have reached their RMD age, under these Proposed Regulations, the amount of the RMD itself will usually be decided by the surviving spouse's age. Which means that surviving spouses who are older than their deceased spouse will need to take an RMD greater than if the spouse had been alive to take the RMD themselves.

In other words, the benefits of being able to delay RMDs as a result of the election will, in many cases, be at least partially offset by the need to take a higher RMD once they actually begin.

When the SECURE 2.0 Act was enacted, many people assumed that a surviving spouse electing to be treated as the decedent meant that, once the surviving spouse themselves died, any of their subsequent beneficiaries would have been treated as if they, too, were beneficiaries of the original account owner, and that those who met the criteria to be Eligible Designated Beneficiaries would be permitted Stretch treatment of distributions from the account over their life expectancy.

Unfortunately, this is another area where it seems the IRS has decided to consider "being treated as the decedent" as not literally being treated as the decedent. As the regulations make clear, if the surviving spouse dies after beginning RMDs from the account, all their beneficiaries will, in effect, be treated as Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries of the surviving spouse. That is, they will calculate annual RMDs with the Single Life Table, using the spouse's age in the year of their death, and crucially, they will be required to fully distribute the account by the end of the 10th year after the spouse's death, even if they would have otherwise met the criteria to qualify as an Eligible Designated Beneficiary.

In sum, the election for a surviving spouse to be "treated as the decedent" (such as it were) does have some benefits in the form of being able to potentially delay RMDs until the deceased spouse would have been required to take them and the ability to use the Uniform Life Table rather than the Single Life Table. But it isn't quite as helpful as we were led to believe since the surviving spouse must use their own age in calculating the RMD amounts and the surviving spouse's beneficiaries will not be treated as Eligible Designated Beneficiaries once the surviving spouse passes on.

Still, in most cases making the election to be treated as the decedent will in most cases be a better choice than not making it, and instead being treated as a "regular" (non-spouse) Eligible Designated Beneficiary taking Stretch RMDs using the Single Life Table. To that end, it's notable that the election will be treated as automatic in cases where the original owner dies before their RMD date, meaning there will be no need for the surviving spouse to 'opt-in' to being treated as the decedent. If the owner dies after their RMD date, the election can also be made the 'default' option by the plan's administrator. And in cases where it's better for the surviving spouse to roll over the account into their own IRA (e.g., when the surviving spouse is younger than the decedent), they'll still be able to do so even after the election is made.

There will almost certainly be many comments and likely some changes to these new proposed regulations before they are finalized. But for now, it seems as though the "be treated as the decedent" election is, in practice, not everything it's cracked up to be.

Given the sheer scope of the new Finalized and Proposed Regulations, it will clearly take some time for advisors to internalize the many intricacies and nuances around planning for retirement accounts, particularly around post-death distribution planning. Because whether the beneficiary is a spouse, a trust, or any other type of individual or organization, the new rules only increase the complexity of the decisions that retirement account owners and their beneficiaries will need to make.

Of course, the irony is that the more complex and taxpayer-unfriendly the regulations get, the more valuable advisors' work becomes in helping clients untangle the web of rules and avoid missteps that could cause problems for years or even decades down the line. And so, while in an ideal world the net effect of legislation like the SECURE Act, SECURE 2.0, and the regulations surrounding both would be to simplify the tax considerations of planning for retirement, in the world we're in, there are plenty of opportunities for advisors who can navigate the rules to create deep trust with their clients. Or, put differently, the more complex Congress and the IRS make things for taxpayers, the more valuable advisors become when they can simplify these issues for them!